As I was watching the Oscars last night, I came to the realization that my exposure to film financing via my own consulting firm SAGA Capital in the 2000s, was probably the most fascinating aspect of my professional career in structured finance. Thus, I decided to spend 2-3 hours after the Oscars collecting my files, pictures, charts, etc and writing the article you are about to read. The glitz and glamour of Hollywood has long fascinated the public. However, behind the red carpets and movie premieres lies a multi-billion dollar global industry, and one that is increasingly seen by investors and financial institutions as a smart place to put their money.

This article will explore how the film industry has matured into an attractive investment asset class, offering high returns, diversification from traditional investments, and recession-proof (but not pandemic proof) revenues. I'll also recount my own journey as a former Wall Street quant working for the CDO group of Deutsche Bank under Phil Weingord, head of Global Asset Securitization at that time. When I left DB and started my consulting firm, I envisioned the potential to apply sophisticated data science techniques to tame the risks and optimize returns in Hollywood film financing, back in the early 2000s.

I founded a firm called SAGA Capital (SC) with two former colleagues. We began researching film financing data and started running all kinds of analytics. Rolling correlations of returns, time series analyses, accounting reviews, Monte Carlo simulations, supervised and unsupervised clustering analysis of certain elements of films and all sort of things at our disposal in our quantitative finance and data science arsenal.

After spending some time in Hollywood, Toronto, London and Cannes meeting with many film producers, accountants, distribution companies and even actors, to our surprise, we uncovered clear statistical relationships between revenues and factors like budget, genre, ratings, creative team and many, many others.

I was all of the sudden showing the results of my machine learning model and intellectual property (intangible) assets pricing models to crowds of film producers and investors in Hollywood and New York, with a great deal of interest.

Along that journey I also met another quant, Thomas Trenker, also ex Deutsche Bank (equity analyst) who was quantifying Hollywood from a different point of view and also quite fascinating. Our path crossed and we cooperated in a couple of film financing deals and more than once we coincided in the same Hollywood social events attended by some of the people we were advising on our approach.

1) My wife with actress/model Patricia Velazquez at a benefit gala in NY 2) Anthony Hopkins at an event in LA, 3) Rachel Weisz at a benefit gala in NY, 4) Courtney Henggeller (Sheldon’s sister in the Big Bang Theory) at my favorite spot in LA, the Sunset Marquis in LA, 5) tequila with my friends Mark Morgan & Jonathan Goldsmith “the most interesting man in the word” at the Petit Ermitage in LA

The "quant engine" that SC developed was a machine learning system that could forecast box office revenues with 80%+ accuracy and could quantify risk factors and recommend aspects for improvement. This became the core of SC's film financing advisory business, but it also had aspect concerning taxation and jurisdiction.

The film financing approach I developed at SC and its potential is covered on the following aspects of this article:

With this quantitative/qualitative approach, SC provided some forms of financing to independent productions in partnership with distributors and financial institutions seeking alpha. Analyzing film projects systematically rather than relying on gut instinct allowed SC to identify promising investments in, for example, the “Fast and the Furious Tokyo Drift”, which traditional financiers and some studios passed on while some progressive hedge funds took positions on it after careful analysis of our work.

Our marketing mix model (a separate ML model based inspired by the work of Dr. Anita Elberse at Harvard Business School and who I thank for her invaluable feedback back then) also optimized advertising spending over time. We were able to calculate the point where additional advertising stopped "lifting" box office revenues, thus avoiding wasted ad expenditures and boosting returns by 10% - 30%.

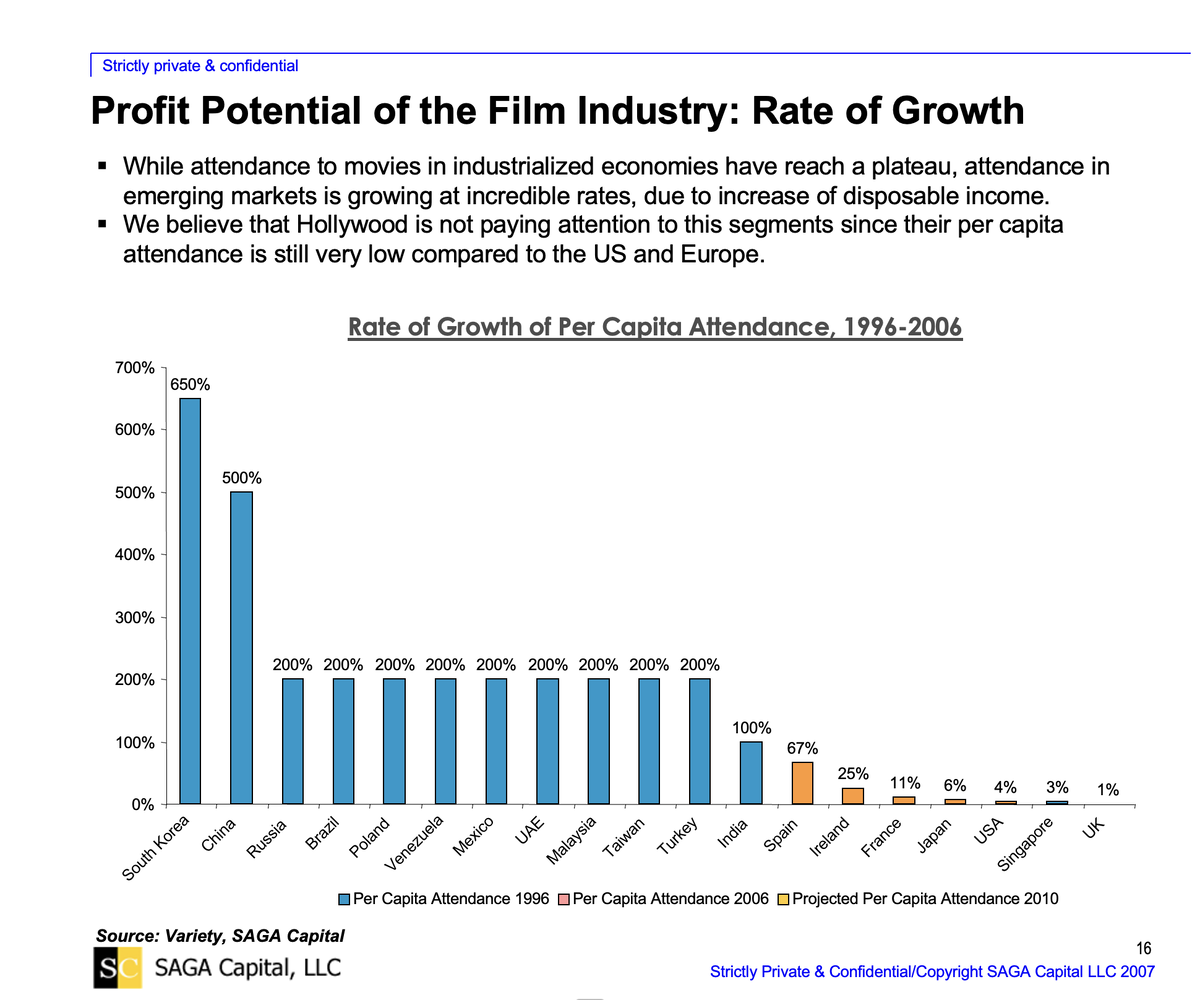

The numbers speak for themselves - the Hollywood film industry generates worldwide revenues exceeding $100 billion annually. US domestic box office takings have steadily risen over the past decade, from $5.5 billion in 1995 to over $10 billion in 2022. International box office revenue now brings even higher amounts of revenue, but that was not always the case.

The 2010s started strong for the domestic box office, reaching an all-time high of $10.8 billion in 2012 driven by major blockbuster franchises like The Avengers and The Dark Knight Rises. However, revenue declined in 2014 and 2015 with fewer mega-hits and growing competition from streaming and other entertainment options. The market rebounded in 2016 and hit a new record of $11.1 billion in 2017 thanks to Star Wars, Beauty and the Beast, and Wonder Woman. But growth then slowed again with signs of franchise fatigue. Despite massive hits, 2018 and 2019 saw small declines. The COVID-19 pandemic further impacted theaters in 2020.

While recovery is now underway overall growth has been slower compared to the 2000s and early 2010s (the "golden period" of film as an alternative investment), and revenue has shown increased year-to-year volatility in the latter half of the decade. Challenges remain for movie theaters but tentpole releases can still drive billion-dollar years, keeping the domestic market substantial. Importantly, traditional cinema releases account for only around 10%-20% of a film's total gross earnings. The explosion in DVDs and rentals in the early late 1990s and early 2000s, along with TV rights, overseas distribution, ancillary revenues, and boom in streaming services, etc. can generate 80%-90% of revenues.

This consistent growth, when many industries struggle during recessions, is why Standard & Poor's regards film as "generally recession-proof". People still seek entertainment during downturns, flocking to cinemas and/or streaming movies when they reduce spending on luxuries

So what makes movies so appealing from an investment standpoint?

In the early 2000s, I saw firsthand how hedge funds and institutional investors were desperate to find uncorrelated return streams offering high yields. Exotic structured products like weather derivatives and insurance risk securitization, where I had expertise in origination and structuring were all the rage.

It struck me that film financing checked all the boxes - high returns, diversification, global growth, and predictable ancillary revenues. Yet it was dominated by subjective Hollywood culture, not financial engineering. I sensed an opportunity to bring institutional rigor and quantitative analytics to this untouched alternative asset class.

If we could statistically model the key variables driving movie success, size the risks properly, and optimize financing structures, film could provide an ideal vehicle for alternative investment portfolios. The challenge was building credible financial models when each movie is a unique creative project. This required finding useful patterns in the data, and definitely "one-off analysis" but with reusable components.

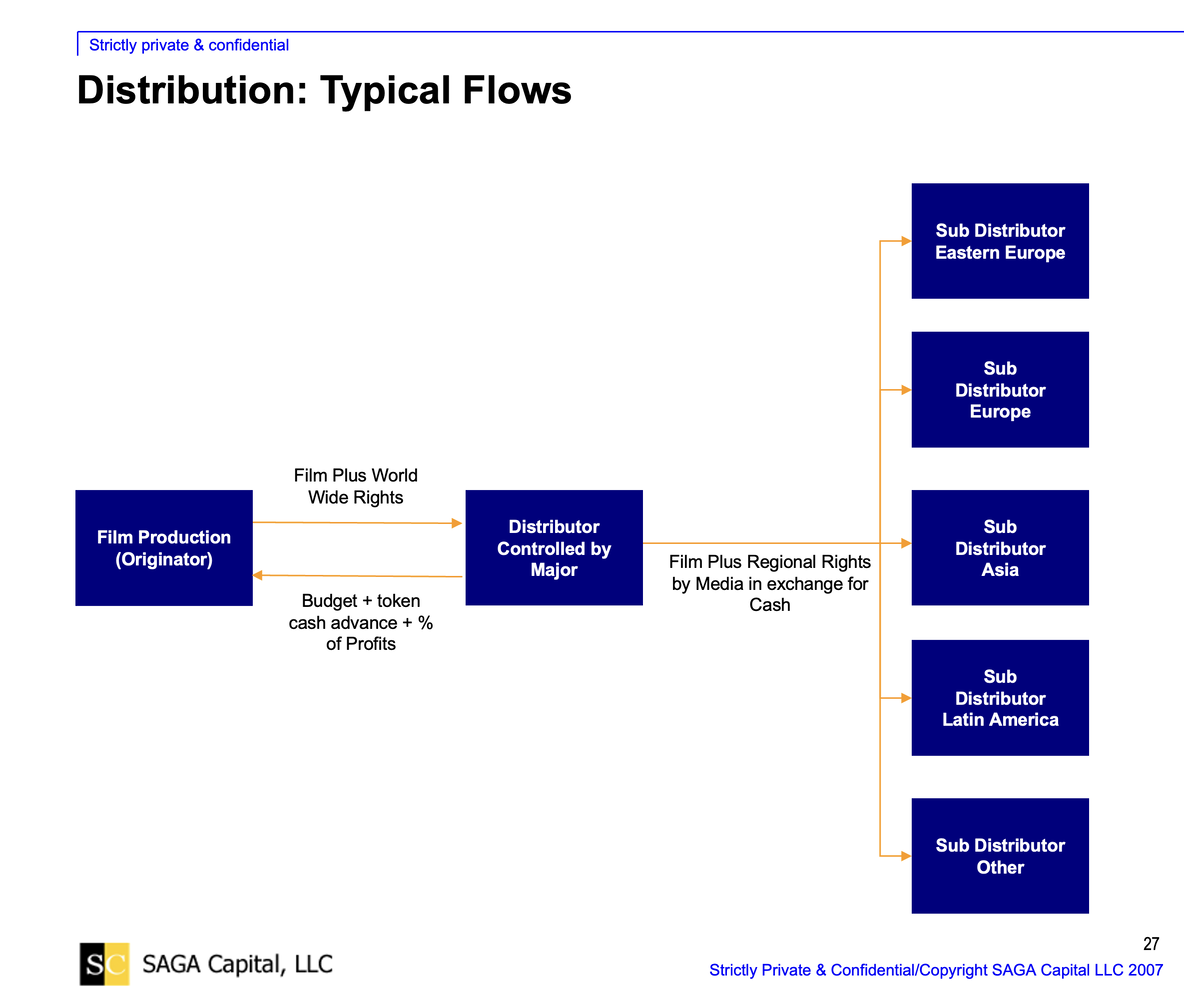

I was introduced to pre-sales by an independent producer who was looking for financing for his slate of films, and I could not believe that what I was seeing was an OTC market for options on intellectual property assets with no pricing model.

Pre-sales are a common financing method in the film industry where the producers sell the distribution rights (let's call it an "options") of a film to foreign distributors before the film is completed. This method helps in securing funds for the production of the film. Here's a detailed explanation of the different aspects:

Example:

Imagine a producer planning to make a film with a budget of $10 million. They might approach distributors in various countries, such as Germany, Japan, and Brazil, and presell the rights to distribute the film in those territories. In a simplified example:

These agreements total $6 million in pre-sales. The producer can then take these agreements to a bank and secure a loan against them, providing significant funding towards the $10 million budget. A completion bond might be taken out to assure all parties that the film will be delivered as promised.

The interparty agreement would then outline the relationships and priorities between the bank, the producers, the completion guarantors, and the sales agents, ensuring that everyone understands their rights and responsibilities.

Presale financing is a complex but vital part of film financing. It allows producers to obtain "leverage" against funding based on the perceived market value of their film, but it requires careful navigation of legal and financial arrangements. One of SC innovations was to produce the first ever pricing model for these options on a territory by territory basis and recommend film backers (hedge funds, investment banks and production companies in our case) what territories to "sell" and which ones to "hold", depeding on market conditions and availability.

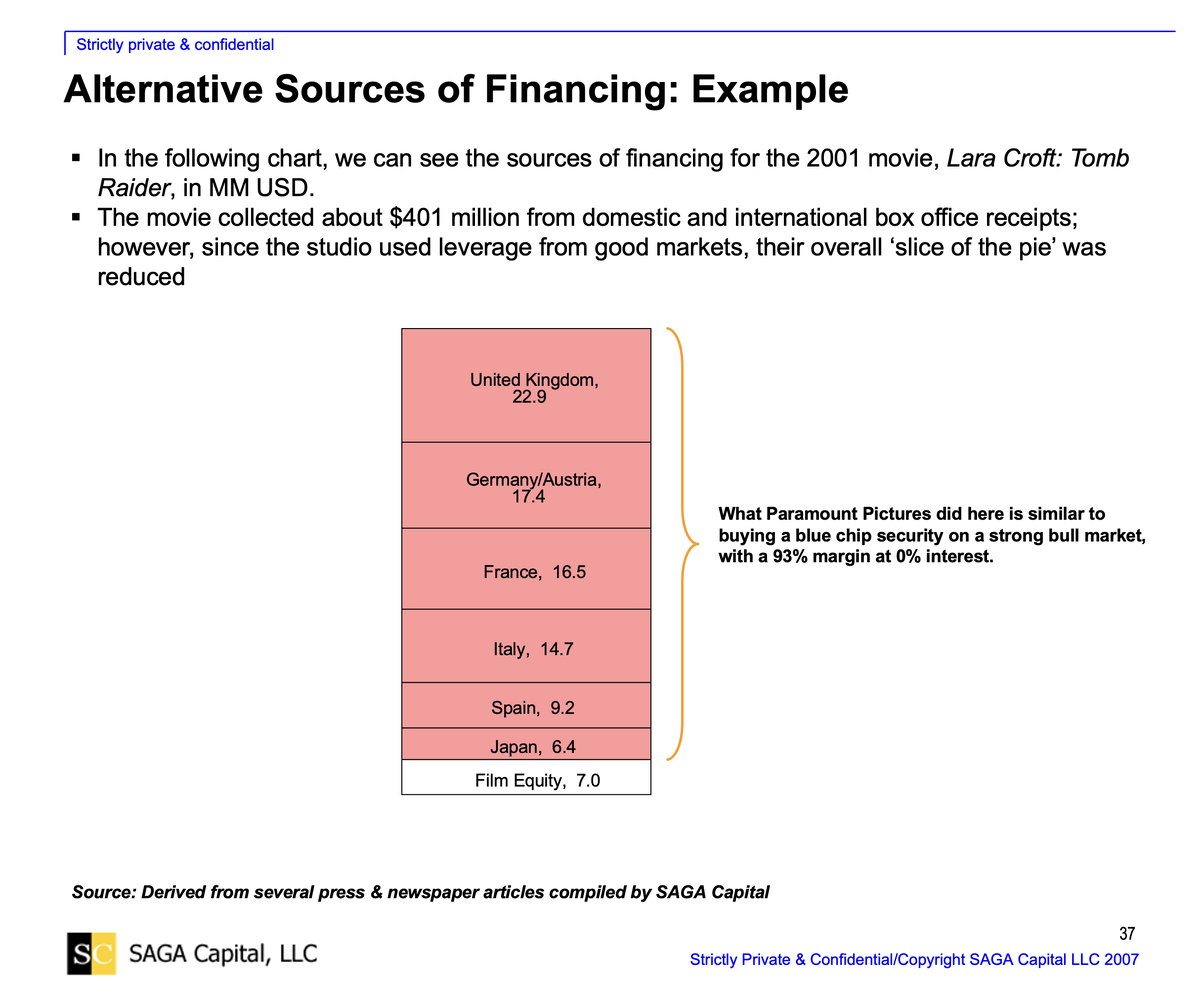

The chart below shows the "pre-sale" funding for film Lara Croft: Tomb Raider with Angelina Jollie and produced by Paramount Pictures.

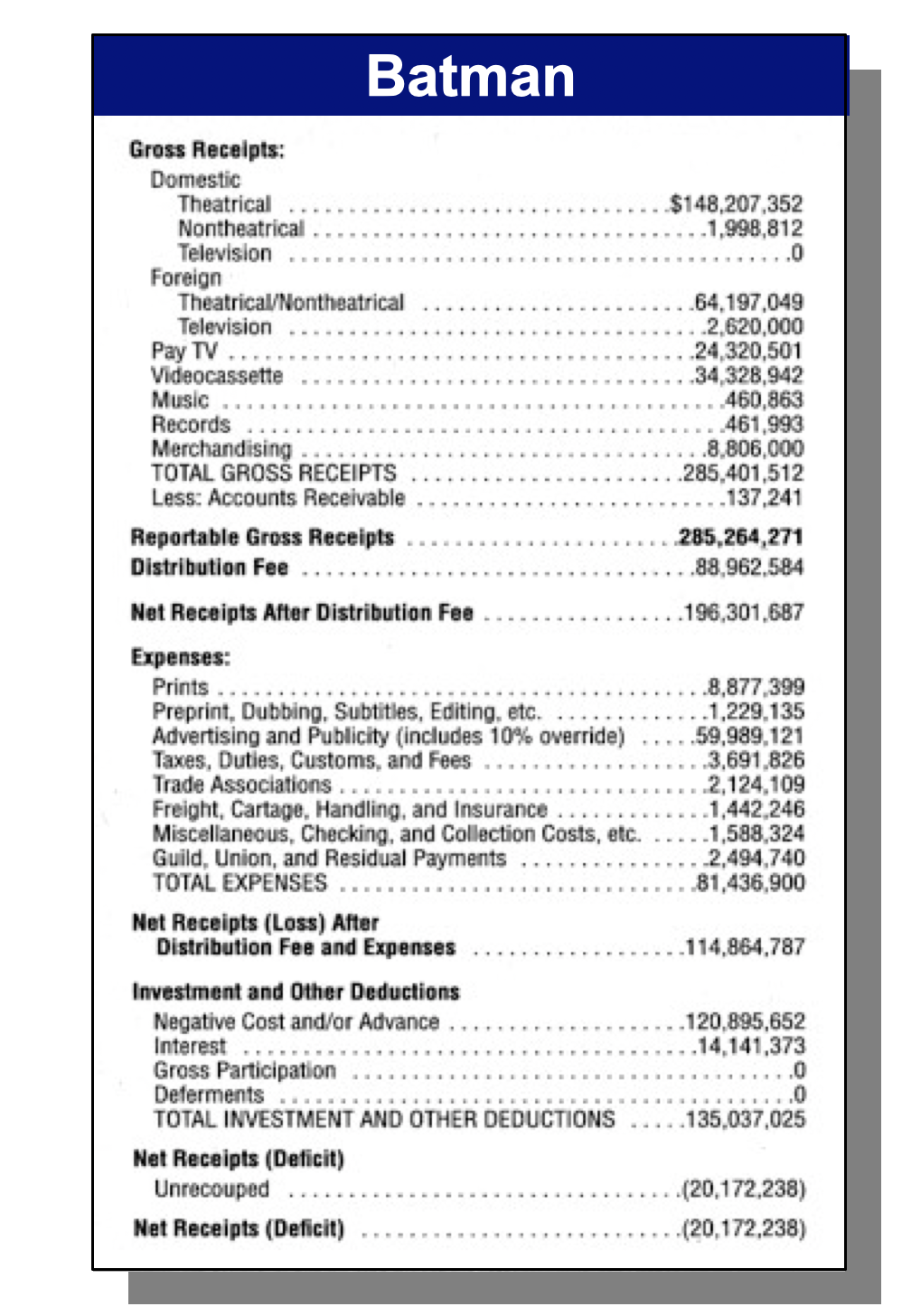

In the complex world of film financing and distribution, Hollywood studios have long been accused of employing creative accounting practices that can leave even the most successful films showing little to no profit on paper. This issue has been a point of contention for many actors, directors, and other creative professionals who often have profit-sharing agreements tied to their compensation.

In an striking example of this practice that SC learned from industry insiders, a movie that grossed $285 million in sales against a production cost of $120 million still managed to show a loss, effectively denying the talent involved any bonus profits. This particular case, presented by Benjamin Melniker and Michael Uslam on behalf of themselves and others against Warner Bros. in Los Angeles Superior Court, is far from an isolated incident.

Ronald Bass, an entertainment attorney-turned-screenwriter responsible for films like "The Joy Luck Club," "My Best Friend's Wedding," and "Rain Man," has negotiated millions of dollars in deals with studios. Despite his extensive experience, he believes it is extremely difficult for movies to reach net profits under the studios' net profit definitions.

Frustration with these practices has led some top talent to venture out and create their own independent production companies in an effort to maintain more control over their projects and compensation. However, these individuals often face significant capital constraints and lack access to sophisticated financing vehicles, and this created an incredible opportunity for structured finance products such as the ones SC was creating.

Notable examples of independent producers who have at some point struggled to obtain financing include Ethan Hawke, Diane Keaton, Tom Cruise, Robert Redford, Anthony Hopkins, and Meryl Streep. But in a rare and impressive feat, Mel Gibson self-financed his film "The Passion of the Christ" entirely with his own capital and realizing an amazing IRR.

The ongoing struggle between creative talent and studios over fair compensation and transparent accounting practices continues to shape the film industry. As more artists become aware of the challenges they face in securing a fair share of profits, there is a growing demand for reforms in how studios calculate and distribute profits. Until meaningful changes are implemented, however, Hollywood's creative accounting practices will likely remain a source of frustration and contention for many in the industry.

5a. The German Tax Shelter Funding Hollywood Budgets in the early 2000s

To help finance mega-budget blockbusters like Lara Croft: Tomb Raider, studios exploited loopholes in Germany’s tax laws. German investors can take immediate tax deductions by investing in a German-owned film rights company, even before a film starts shooting.

The studio sells the film rights to this German firm, then leases them back for production. The Germans profit from tax savings, while the studio gains this upfront funding—often 10% above their buyback price—all at zero risk or cost.

For Paramount’s Tomb Raider, selling the rights to a German firm netted enough funding to to cover the stars’ salaries right off the bat. And Lara Croft's was one of many films with paper profits even before filming a single shot.

So SCl started to combine its quantitative model with some of the unique elements of "tax arbitrage".

5b. The US Film Tax Credit Programs (Federal and State) of the 2000s: Competing with the German Program

In the early 2000s, the United States government and several state governments introduced tax credit programs to compete with the successful German tax shelter program and to encourage film production within the country.

At the federal level, the American Jobs Creation Act of 2004 introduced the Section 181 tax deduction. This allowed investors to immediately write off the costs of film and television productions up to $15 million, or $20 million for productions in economically depressed areas. The aim was to incentivize domestic film production and counter the appeal of foreign tax incentives like those offered in Germany.

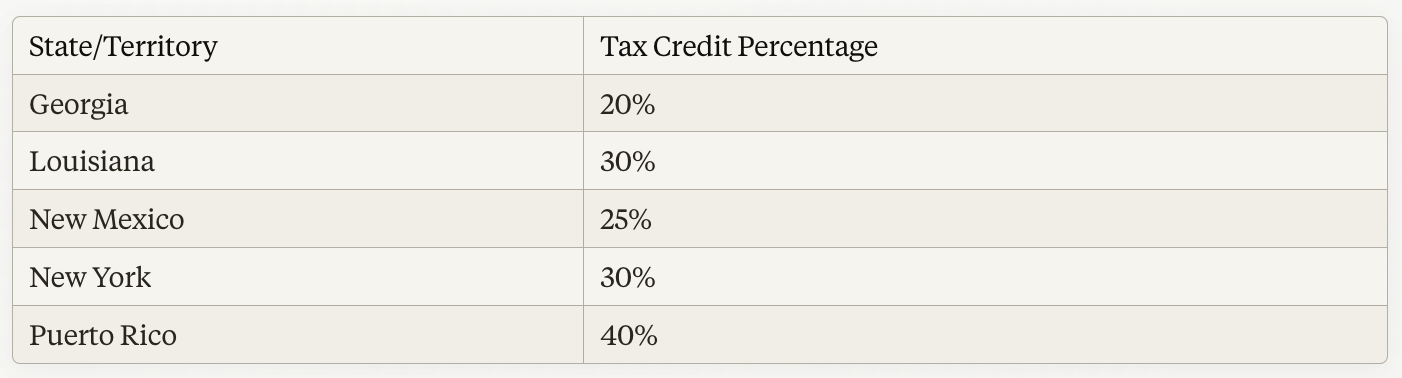

Simultaneously, many states began implementing their own film tax credit programs to attract productions to their locations. States such as Louisiana, New Mexico, and Georgia were among the pioneers, offering generous tax credits ranging from 20% to 40% of a production's qualified in-state expenditures. Producers could apply these credits to their state income tax liability or, in some instances, sell them to third-party taxpayers for immediate cash.

The combination of federal and state tax incentives helped make domestic production more competitive with international alternatives. By the end of the 2000s, a majority of states had implemented some form of film tax credit program. This led to increased competition among states to secure high-profile productions, which were seen as a source of job creation and local economic growth.

Although these programs have faced criticism regarding their cost-effectiveness and overall economic impact, they have undoubtedly played a crucial role in shaping the landscape of film and television production in the United States throughout the 2000s and beyond.

This also provided SC's first source of revenue in the film financing business as well as opportunity to team up with some well known producers. This is how it worked:

Imagine the following scenario: producer "A" from Hollywood films a movie, in let's say Puerto Rico, and its cost is $10MM USD all spent there (for simplicity's sake). Typically this producer returns back to CA with a film made and hopefully some future ROI for the investors (usually shareholders in an LLC created just for the film). But unbeknownst to producer "A", his film qualifies for a 40% "tax credit" from Puerto Rico, applicable to tax liabilities in Puerto Rico. But wait, this producer filmed the movie there because it was the perfect location for his film, not because of any tax credit.

Enter SC advisory service: turns out that with some paperwork and nominal fees, a film tax credit worth $4MM can be issued for the benefit of producer "A. This tax credit can be used against tax liabilities in Puerto Rico and is 100% transferable.

So SC matched, let's say an investment bank such as Lehman Bothers and/or Goldman Sachs with that transferable tax liability, for which they paid, let's say 80% of face value ($3.2 MM in this example).

With this structured trade, a) the Hollywood producer obtained a $3.2MM "discount" in the cost of his production thus enhancing the risk/return profile to the investors in the production, b) the investment bank reduced its tax liability in Puerto Rico by $800,000 and paid SC a $200,000 for the origination of the deal.

I registered SC with all the film commissions of the different states of the US that had such programs and developed relationships with several key independent film producers in the USA, and with certain divisions of banks such as Lehman, Goldman, and a few hedge funds who wanted exposure to film assets. There was a steady deal flow of assets with almost no competition.

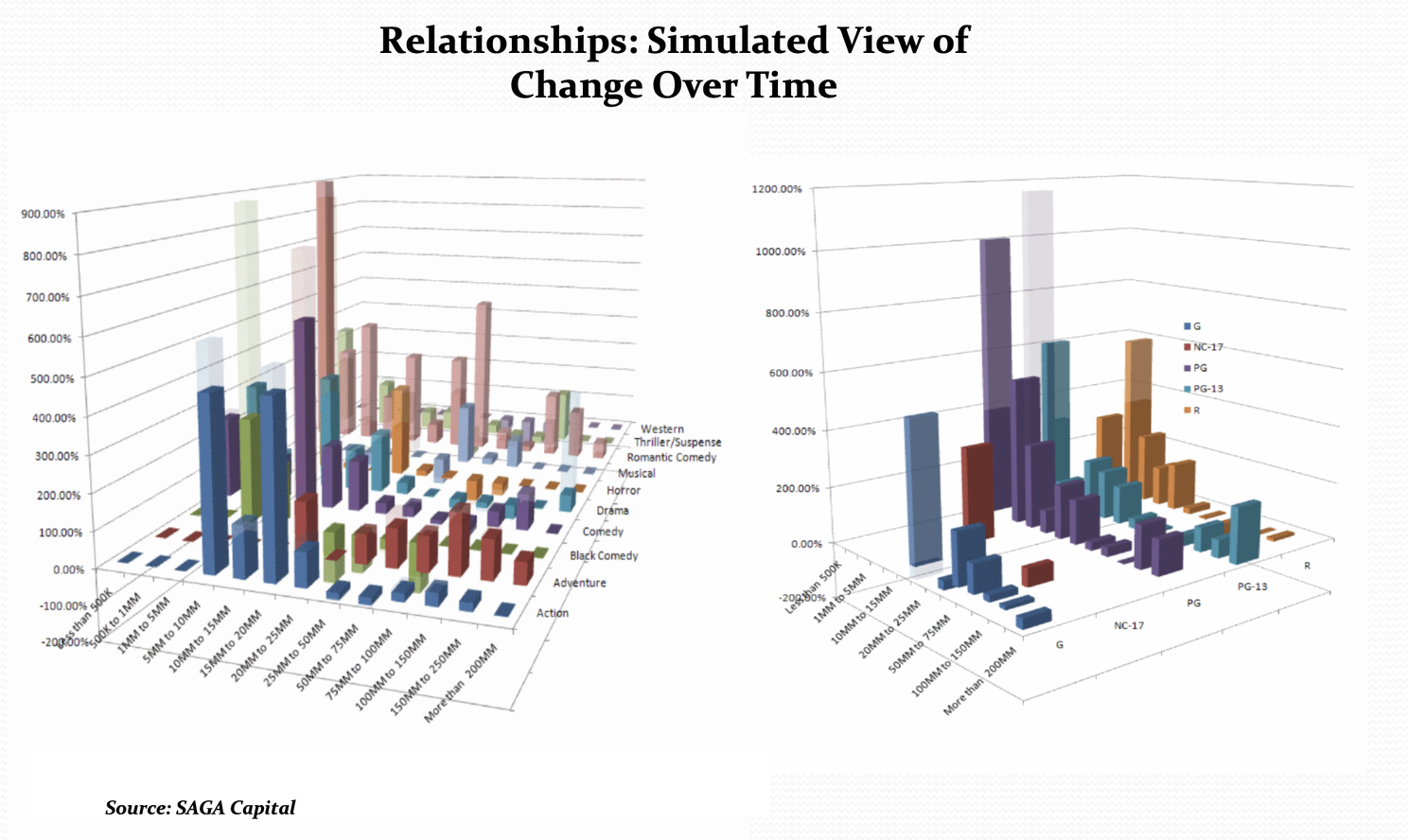

Leveraging our quantitative models and advisory services, SC provided financing for slates of films from independent producers. Our data science approach allowed for careful calibration of risks and returns in an industry where finance and analytics had been an afterthought. Without going into the details of the model and its time series aspects, the chart below gives and idea of some of the quantitative factors we were tracking

Seeing the success of our models and film tax credit advisory fees, major investment banks began acquiring film rights as asset-backed securities for yield-hungry hedge fund clients. I was eventually recruited by Lehman Brothers to be part of their team structuring High Yield credit products, bringing SC's IP to the bank. Needless to say, applying statistics and algorithms to an art form like filmmaking raised skepticism at first from old-guard Hollywood insiders and even some bankers. I still remember some producers that took personal offense that a machine learning model was weeding out risks better than them, and even made derogatory comments about the analytical approach. C'est la vie

Aside from advising some prominent hedge funds around what exposure to take in slate of films that we had quantified at their request, we began experiment with a more "dynamic" concept. Unfortunately, I can't speak about specific examples, but I can speak of a "sub product" of our analysis.

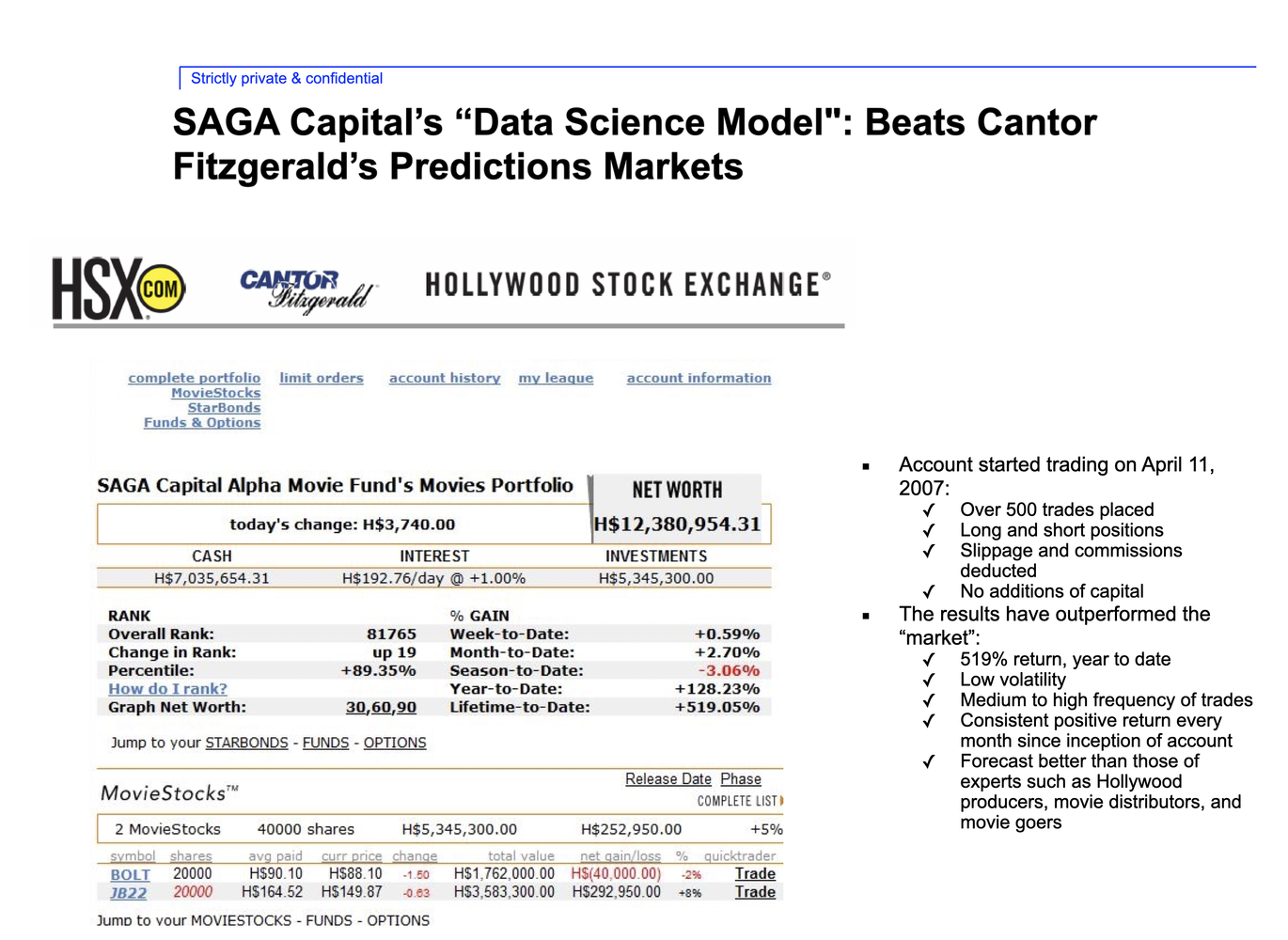

In an astonishing proof of concept, we began trading a simulated film investment portfolio in 2006 on the Hollywood Stock Exchange (HSX) - a "prediction market" where investors bet on movie performance. Our purely quantitative model achieved a +100% return in 9 months trading HSX movie stocks despite no fundamental knowledge of the films themselves.

The Hollywood Stock Exchange (HSX) was a web-based prediction market which players used simulated money to buy and sell "shares" of actors, directors, upcoming films, and film-related options. It was developed by Cantor Fitzgerald, a well known financial services firm. With backing of Lehman Brothers, the HSX had applied to the US Commodity Futures Trading Commission, an independent agency of the US government created in 1974 that regulates the U.S. derivatives markets, which includes futures, swaps, and certain kinds of options. The brainchild of Howard W. Lutnick, Cantor's CEO, the HSX concept was way ahead of its time, but the timing was not right. Howard is some sort of renaissance man, with a history of resilience, compassion, and determination in the face of adversity, one of the most creative people in today's world of finance.

The HSX and the associated concept of trading movie box office futures were seen as a way to hedge the financial risks associated with the ever-increasing costs of producing movies. Here's how it was intended to work:

With 1) SC track record in the quantification of films revenues well in advance of their release, 2) an interesting supply of film tax credit in the US, 3) proper structuring and film distribution and advertising agreements in place, I sought to raise a few million of seed capital to produce films in the "sweet spot" in term of talent, budget and jurisdictions, and also hedge position in the upcoming CFTC approved HSX Futures Exchange. An ABS "quants dream come true": origination, distribution, and hedging of the asset with a quantitative edge.

However, the idea of trading real-money futures on box office performance faced significant opposition and regulatory hurdles. Critics argued that there were concerns about the ethical implications of betting on the success or failure of creative works.

As a result, the real-money trading aspect of this concept never fully materialized, and HSX remained a prediction-market with no money involved. The underlying rationale, though, reflects a sophisticated attempt to apply financial risk management techniques to the unpredictable world of entertainment.

Back then, our hands-off algorithmic approach delivered returns far beyond human players on HSX relying on insider knowledge, skills and intuition. SC models deployed as an algorithmic trading tool inside HSX market simulation demonstrated the immense power of data mining for predicting box office success based solely on statistics.

It is sad to see that all the hard work of Howard Lutnik and my friend Rich Jaycobs , President of Cantor Futures Exchange di not come to fuition, the whole concept of trading intangible in a regulated market was (and still is) very progressive and a quantum leap in the creation of market efficiencies & price discovery mechanisms.

In the midst of the thriving era of film tax credits and innovative financing strategies, the global financial crisis of 2008 dealt a severe blow to the entertainment industry. One of the most significant events during this period was the bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers.

Lehman Brothers had been actively involved in packaging and marketing complex film financing deals, often utilizing tax credits and other incentives such as the ones I was sourcing before joining the firm.

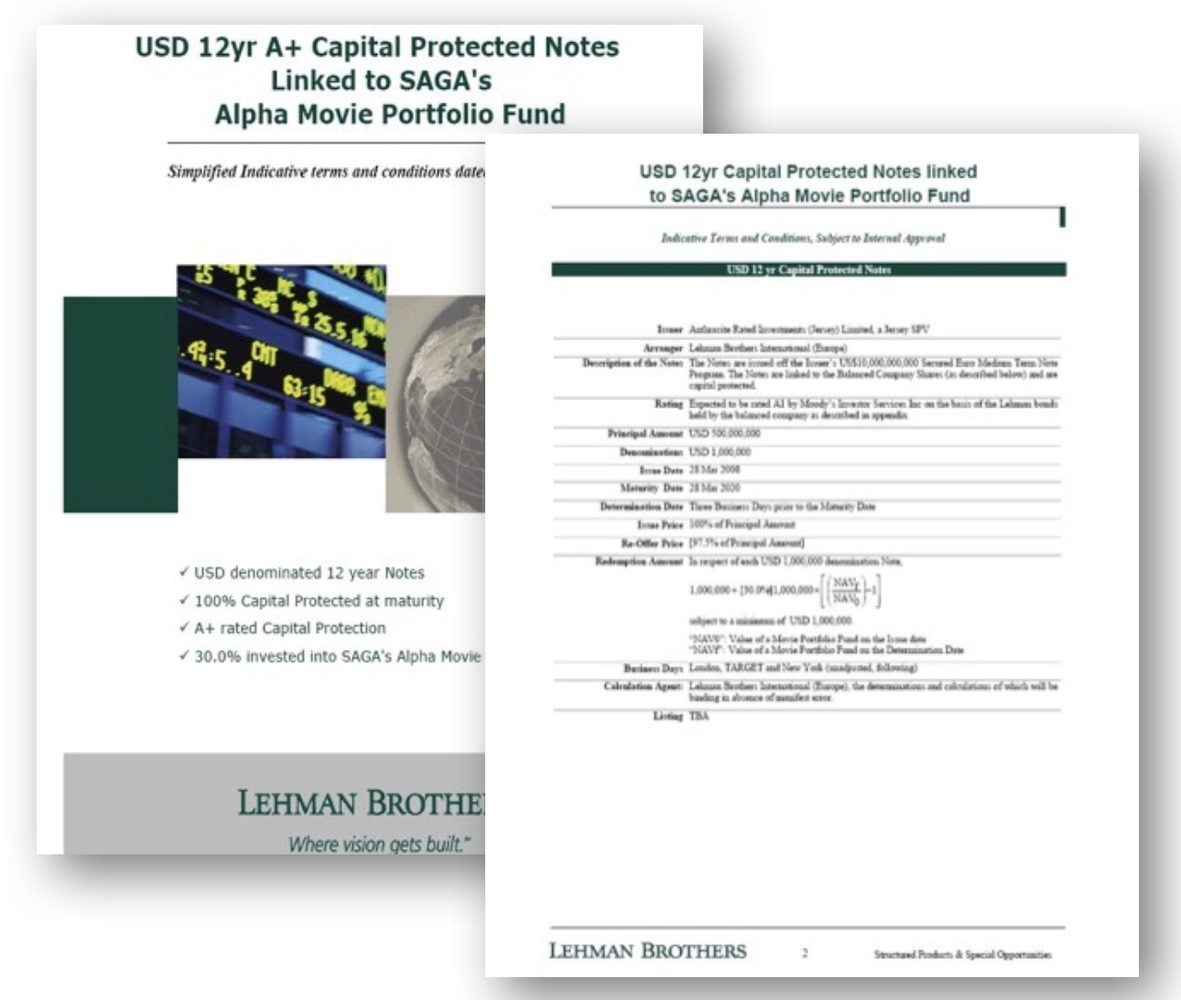

One such structures was, as an example among many, a USD 12yr A+ Capital Protected Notes linked to SC Alpha Movie Portfolio Fund, which offered 100% capital protection at maturity, with US Treasuries as collateral. This innovative structure aimed to provide returns linked to a private equity fund investing in film, while also offering credit rating opinions from third parties to ensure due diligence on qualitative and quantitative aspects of the structure.

However, this groundbreaking deal, along with many others, never came to fruition as Lehman Brothers collapsed in September 2008, sending shockwaves through the financial markets and leaving the future of numerous film projects in limbo. I transitioned to Barclays Capital but they had no interest in such structures, and market conditions for credit risk were sub optimal.

The sudden absence of Lehman Brothers as a major facilitator of film financing deals created a void in the market, and other financial institutions were hesitant to step in amidst the economic uncertainty. This led to a significant reduction in the flow of capital into the film industry, forcing studios and producers to scale back their plans and seek alternative financing methods.

Looking back, it was an exciting journey to bring institutional finance and Big Data analytics to the insular world of Hollywood. The film industry has now fully embraced data-driven decision making. For investors, that makes financing movies an even more tempting opportunity blending art and science for potential blockbuster profits. The cameras are always rolling somewhere, and the data science revolution on the business side of Hollywood is just beginning.

As the film industry grapples with the challenges of creative accounting and fair compensation, a new frontier is emerging that could revolutionize the way movies are written and produced. Generative AI, particularly Large Language Models (LLMs), are showing immense potential in the realm of script writing and content creation.

My company SGX Analytics is currently training advanced LLMs, such as SCORA (SCriptwriting Optimized Recurrent Architecture), specifically designed to write compelling and original movie scripts. By leveraging vast amounts of public data and sophisticated machine learning algorithms, AI models such as SGX's SCORA can generate coherent, emotionally engaging, and structurally sound screenplays across various genres. Coupled with, for example, SORA, a groundbreaking text-to-video model developed by OpenAI, designed to generate realistic and imaginative videos from text prompts, the implications are far reaching.

Additionally, these models could help to democratize the screenwriting process, enabling aspiring writers to create high-quality scripts even if they lack extensive experience or industry connections.

However, the use of generative AI in film production also raises important questions about creativity, authorship, and intellectual property rights. As these models become more advanced and autonomous, there may be concerns about the role of human writers and the potential for AI-generated scripts to displace traditional screenwriting jobs.

Despite these challenges, the potential benefits of generative AI in the film industry are significant. By streamlining the script development process and reducing costs, AI-assisted screenwriting could open up new opportunities for independent filmmakers and smaller production companies. Moreover, the ability to generate a wide range of script variations and adapt to specific audience preferences could help studios to create more targeted and successful films. Back in 2012, with my semantic search engine Ttwick I attempted a very basic form of this, in a JV with now my friend Mark Morgan, but the computational cost was out of reach for the resources at that time. Mark Morgan is a film producer known for his work on the "Twilight" movie and the subsequent films in the series which became a global phenomenon and grossed hundreds of millions of dollars at the box office.

Mark knew that my patent applications to the USPTO was the closer "thing" out there for the future vision of his production company and that's why he contacted me back then and created a JV for his vision of AI applied to the creative aspects of film production. Mark's work has had a significant impact on popular culture and he has shown interest in various personal projects, including acquiring rights for a sci-fiction books and AI applied to creativity.

As I mentioned the technology was not there yet 10 years ago, but now we are at a point where many of the ideas of Hollywood creatives like Mark can be brought to reality, and my consulting firm is already cooperating with professionals like Mark in the area of generative AI, where we also have our own.

The future of entertainment is exciting!